Hurricane Harvey dropped nearly 52 inches of rain on southeastern Texas and beyond. Standard home and business insurance policies exclude flood damage as a named peril. Few people are covered by separate flood insurance policies. And key parts of the National Flood Insurance Program are set to expire on September 30, unless....

On August 30,

Tropical Storm Harvey blasted through the single-storm total rainfall of any

storm ever recorded in the continental United States: 51.88 inches over Cedar

Bayou. All equivalents to the 24.5 trillion gallons dumped onto Texas and Louisiana are staggering. That volume exceeds Houston’s average annual rainfall in less than a week. It approximates 15 percent of the volume of Lake Erie. That’s a year’s flow over Niagara Falls. It's enough to cover the entire state of Arizona a foot deep.

|

Thousands of square miles

were flooded by Hurricane Harvey. More than 80 percent of these homes are not

protected by flood insurance. Credit: The Washington Post

|

The nation’s

attention is riveted on Houston as the fourth largest city in the nation and

the center of the country’s petroleum industry. But as history reminds us:

Harvey is flooding areas far beyond Houston. It is also devastating the lives

of people in surrounding areas of Texas with three and four feet of water: in a

fateful echo of the 1913 flood, Dayton, TX was deluged with an unfathomable

49.23 inches.

Louisiana and neighboring states were also hard hit—including locations impacted

by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita almost exactly 12 years ago (see “How Does Hurricane Harvey Compare with Katrina?”

and “Katrina + 10: Once and Future Disasters”).

|

Harvey

dumped more than four feet of rain on Dayton (!),

Texas; see video on YouTube |

However, if shivering flood sufferers are consoling themselves by clinging to a warm hope that their homeowner’s or business insurance will make them whole, the chilling reality is: some things have not changed since 1913. They may be dead in the water.

Scary facts to

contemplate:

Home and business insurance policies

do not cover flooding

Indeed, typical policies almost always have a

specific exclusion not only for flooding but for any type of groundwater intrusion—including

from such ordinary causes as backed-up sewer mains or snow melt from high

drifts piled against foundations. Obtaining protection against any source of

groundwater requires a separate flood insurance policy.

One reason

private insurers eschew covering flooding on their own is that, unlike such

disasters as fire that often affect only one or a few houses in a residential

area, flooding can devastate square miles at a go: as of August 31, Harvey has

inundated nearly 29,000 square miles with at least 20 inches of rain, and many

times more area at lesser but still monumental volumes of water. Thus, major floods represent

a terrific risk to an insurer.

|

Harvey inundated tens of thousands of square miles to

unprecedented depths. Credit: The Washington Post |

To ascertain

flood risk in various locales and to price premiums, the NFIP conducts surveys

and studies along coastlines, waterways, and other places to identify areas

prone to floods or flood-related hazards (such as storm surges, tidal waves,

mudslides, flood-induced erosion, etc.). Such flood risk zones are plotted on Flood

Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs). These maps focus on identifying Special Flood

Hazard Areas (SFHA): areas having a 1% or higher chance of flooding in any

given year, also stated as being at risk of flooding during a “1-in-100-year

flood.”

|

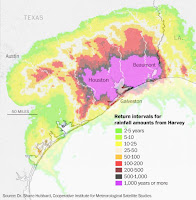

Harvey has

been rated as a once-in-a-

millennium event. Credit: The Washington Post |

Because flood insurance is not universally required like other homeowner and auto insurance, people underappreciate their true risk—indeed, perhaps are lulled into a false sense of security that they have no risk.

Woe to them,

because…

…flood risks are greater than most

think

Many people

did not take probability theory in high school math (or don’t remember it if

they did). So here’s an eye-opening refresher news flash: a 1-in-100-year flood is virtually guaranteed to occur far more often

than once a century. Indeed, the way the mathematics of probabilities works

out, during the course of a 30-year

mortgage of a property in a SFHA, there is a 26% chance the home will be

flooded. That’s better than one chance in four, folks. Them’s betting odds.

A similar

situation also holds true for supposedly lower-risk regions, such as those

designated as 0.2% zones (a 1-in-500 flood). And nothing about the odds

indicates when. Indeed, two 100-year

or 500-year events could—and have—happened in back-to-back years: Harvey itself is Houston’s third 500-year (or greater) flood in three years after its

two Memorial Day floods in 2016 and 2015.

|

Two dozen

so-called 500-year floods have befallen various

places in the United States since 2010. Credit: The Washington Post |

The rainfall intensity of Harvey is now rated as a 1-in-1,000-yearflood event for Houston—that is, a flood of such great magnitude as having just

a 0.1 percent chance of happening in Houston in any year.

Upshot: either

because of ignorance of the actual risk or of the necessity for a separate

policy or because the insurance is optional, only a meager 12 percent of U.S.

homeowners nationwide carry flood insurance. The percentage is a bit higher in the south (especially in Florida), but even

in flood-prone Houston more than 80% of homeowners have not seen fit to

take out flood insurance.

That means that for four out of five Houstonians, their Harvey-ravaged

homes are likely a dead economic loss. If they choose to rebuild, it could mean

bye-bye to retirement savings…

(FWIW, tornadoes,

high winds, and hail may be covered by standard homeowner policies, depending

on the policy and the insurer, but earthquake damage is also often excluded; the only way to know for sure is to check your policy. It is also important

to ensure that the limits to your coverage are high enough to realistically

cover the cost of repair or replacement.)

Key parts of the National Flood

Insurance Program are due to expire

Unless reauthorized or extended by Congress, come September 30 (2017), the NFIP can no longer write any new flood

insurance policies; moreover,

existing policies would continue only until the

end of their one-year terms, and then terminate. The authorization of

appropriations to continue mapping flood hazards also would expire, including

any programs to update older flood maps to take into account the effects of

development or climate change. And the authority for the NFIP to borrow funds

from the Treasury—to, among other things, make good on claims submitted from

Tropical Storm Harvey—would be reduced from $30.425 billion to $1 billion. For

details, see the July 25, 2017 Congressional Research Service report R44593 Introduction to the National Flood Insurance

Program (NFIP).

|

Top 10 flood

insurance payouts.

Credit: Insurance Information Institute |

Existing premiums do not reflect the full risk of actual losses to floods, especially in

the context of rising sea levels and trends toward increasing intense rain

events—a shortfall that increases the federal exposure to risk. At the same time, affordability

of premiums has been a political hot potato, especially from people who want or

need to stay in an SFHA for whatever reason: because it’s all they can afford,

or because they enjoy a great view, or because the property has been in the

family’s hands for generations, or simply because they do not grasp the

magnitude of their actual physical risk.

Sea level rises, coastal cities sink, rainfalls intensify

Houston, the

Gulf Coast, and much of the entire east coast is facing a triple whammy as the

result of measured and predicted climate change.

First,

global sea level is rising—and quickly: 3.4 mm per year. A few silly millimeters

may not sound like much, but that rate amounts to 1.3 inches per decade

worldwide. There are two causes, both stemming from the warming of the planet: first,

the oceans (which are absorbing 90 percent of the warming) expand as the result

of absorbing thermal energy (thermal expansion is how non-digital mercury or

liquid fever thermometers work); second, the volume of water in the oceans is

increasing as Arctic

and Antarctic

ice sheets melt.

|

Just since

1993, in less than 25 years, sea level around the entire planet has risen 3.4

inches, Credit: NASA

|

Second, there’s

an increased likelihood of more powerful hurricanes with higher wind speeds.

Moreover, as warmer air can hold more moisture, even milder tropical storms are

likely to bring increasingly intense rainfalls.

Third—and

less appreciated, but in some places more significant—the land on which many coastal

cities are built is subsiding (sinking) as the result of the pumping of fossil fuels and groundwater from underground

reservoirs. When the fluids are removed, the overlying ground layers sink

lower, exacerbating the effects of flooding from higher sea levels. Nowhere is

that as pronounced as in the cities of, wait for it, Houston and Galveston.

A Hurricane Harvey is not necessary

for a disaster

Even before

Harvey, insurers have been growing increasingly concerned about this juggernaut

“perfect storm”

confluence of events. In April (2017), the American Academy of Actuaries

concluded: “There is an increasing awareness among various constituencies

(regulators, legislators, consumers, insurers, real estate agents) that too

many uninsured homes are subject to devastating losses from flood events, and

the NFIP alone cannot solve the problem. This is true today, and will be even

more true if changing conditions result in rising sea levels and/or more

extreme rainfall events in the future.” (The

National Flood Insurance Program: Challenges and Solutions, April 2017, p.

77)

|

Far less rain than Harvey

dropped on Houston can cause record flooding in colder northern regions of the

nation. A century of weather data indicate that intense rainfall events over

the Ohio Valley and Midwest are increasing both in frequency and intensity.

Because the Easter 1913 storm system brought the flood of record to Indiana and

Ohio, data from it set a benchmark for the question “how bad could ‘extreme’

become?” (see “Benchmarking ‘Extreme’”)

Credit: NOAA; Trudy E. Bell

|

It is time

for clear-sighted recognition of the reality of the stark words of FEMA itself,

“Everyone lives in a flood zone.”

Floods can happen in unexpected places—even places where rainfall is not

intense, or even is completely absent. In

the U.S. Southwest, for example, flash floods from cloudbursts in distant

mountains can rush through downstream desert areas that haven’t seen a drop of

rain (that’s why campers should never set up a tent in an arroyo or dry stream

bed even if the banks look like an attractive shelter from wind). Flash floods

in downstream dryer areas can also happen with springtime melting and bursting

of upstream ice dams. In urban areas, the construction of impermeable surfaces

such as parking lots and pavements increase the speed of runoff and impede the absorption

of rains into soils—and the hardening of riverbeds or coastlines with riprap

(concrete blocks) can redirect flooding onto neighboring lands.

And as

anyone who has endured a household flood can attest, even a little bit of water

can wreak thousands of dollars in property damage: just imagine what flooring,

furniture, and electronics would need to be repaired or replaced in your own

home if your living room and bedrooms were ankle deep in muddy floodwater contaminated

with sewage and chemical toxins. Moreover, water has so much mass that even two

feet of rushing water can sweep away a car (as well as ruin the engine and

interior).

Upshot: most

of us are at greater risk of financial loss from flooding than we recognize.

Even though no one anticipates having a house fire or getting into an auto

accident or needing surgery, most adults recognize that the risk of such events

is not zero, and that any such event could be financially catastrophic

(assuming we lived); so we routinely carry homeowner, auto, and medical

insurance to protect ourselves against financial ruin. Even if we never make a

claim, we rest easier at night with peace of mind—and if disaster falls, we are

thankful that our loss is limited to just a deductible.

Yet somehow we don’t

recognize our same non-zero physical and financial risk to flooding—even if we

live near coastlines or other water, as much of the nation does. Strong economic and risk-reduction arguments could be made in favor of encouraging

all homeowners, renters, and business owners to mitigate their risk to floods as they already do against other risks—both to protect themselves and to ensure the viability of national flood insurance while keeping premiums low.

©2017 Trudy

E. Bell

Next time: Desperate Medicine

Selected bibliography

Bell, Trudy

E., The Great Dayton Flood of 1913, Arcadia Publishing, 2008. Picture

book of nearly 200 images of the flood in Dayton, rescue efforts, recovery, and

the construction of the Miami Conservancy District dry dams for flood control,

including several pictures of Cox. (Author’s shameless marketing plug: Copies

are available directly from me for the cover price of $21.99 plus $4.00

shipping, complete with inscription of your choice; for details, e-mail me), or order

from the publisher.