The violent tornado that ripped through southern Terre Haute, Indiana, on Easter night, March 23,1913, may have been more than one twister, and its full path of destruction extended over 25 miles

Lightning crashes repeatedly, luridly lighting the

parlor where John Hanley and his family were trying their best to ignore the

violent thunderstorm and enjoy being together the rainy night of Easter Sunday 1913. Then around 9:45 PM, over booming thunder and howling winds and

drumming rain, Hanley hears a growing roar of what

|

| Oil painting, possibly of the Terre Haute tornado, was featured as the cover of a leaflet by the New York Underwriters Agency advertising tornado insurance. The unidentified location may have been of a rural area southwest or northeast of Terre Haute itself. If so, artistic license is liberal. The actual tornado struck not in sunlight but well after dark—nearly 10 PM Easter night—in the midst of horrific lightning and torrential downpour, and very likely people were not running across farm fields so near it. Credit: Ray Thomas collection of postcards on the 1913 flood |

sounds like a

fast-approaching express train. He opens the front door—and beholds a towering

tornado just blocks away, bearing down in his direction and sweeping up whole

houses in its fury.

No time to run for the storm cellar—. Yelling he

knows not what, Hanley gathers his family around him in the small hall to huddle

behind the strong front door and its protective outer storm door. Seconds later,

heavy timbers fly through the parlor window and across the room in a cascade of

shattering glass. In moments, the beautiful home is wrecked, along with

Hanley’s three-story warehouse of awnings and construction materials behind it.

Had the family remained seated in the parlor, all five would have been killed.

|

| The destroyed Hanley house likely looked

something like the Dix house, shown here, the morning after the tornado roared

through Terre Haute. Credit: Terre Haute’s

Tornado and Flood Disaster, Wabash Valley Visions and Voices |

|

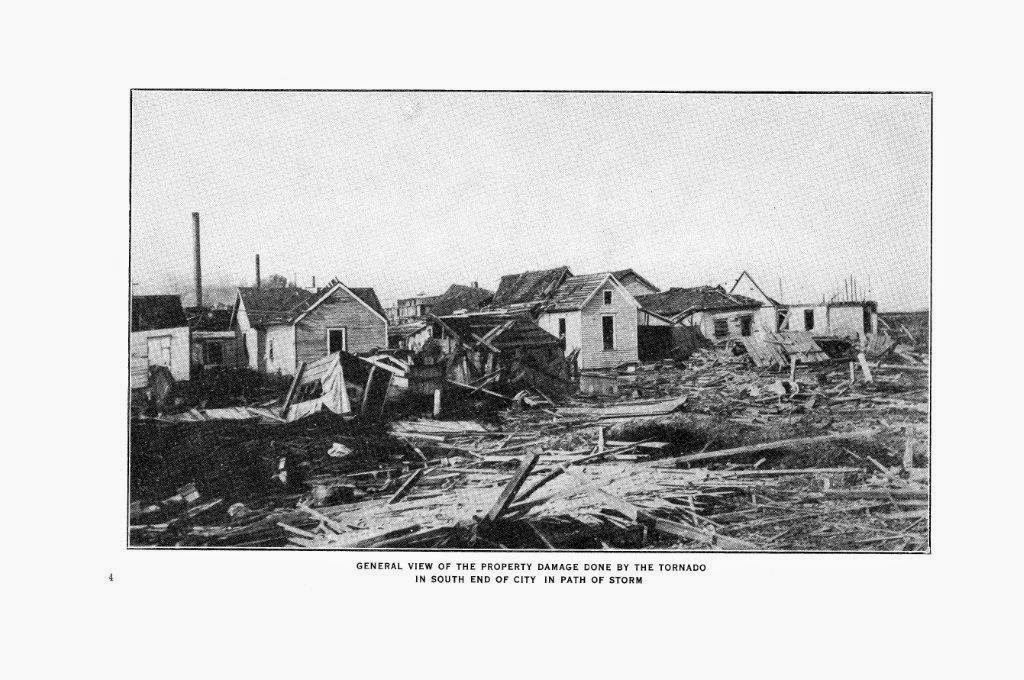

Wide-angle view of a few blocks of

destruction a day or so after the Terre Haute tornado. Note that many people

had umbrellas, as heavy rains were continuing, and in the next day or two

flooding was widespread. Credit: New York Underwriters Agency advertising leaflet

in Ray Thomas collection of postcards on the 1913 flood

|

Reconstructing

Terre Haute’s disaster

One long-standing mystery to me has been the fact that today

the Terre Haute tornado is remembered just for striking one portion of one

city, as if it touched down there and nowhere else. Moreover, text references

to it both then and now as “the Terre Haute tornado” imply the assumption that

it acted completely alone. Yet, violent tornadoes are more typically part of a

larger rotating regional-scale supercell thunderstorm system that tends to

generate multiple tornadoes—as indeed happened four hours earlier that same

night Easter Sunday, 1913 in Omaha, Council Bluffs, and elsewhere across

Nebraska, Iowa, and Missouri (see “‘My Conception of Hell’”).

And as strong vortices, they also tend to persist along paths miles long.

|

The Terre Haute tornado

destroyed the factory buildings of the Root Glass Works, but did not destroy

the company itself, which two years later (1915) went on to design and patent the iconic Coca Cola bottle, this year celebrating its centennial. Credit: Engineering News

|

So for years, my big questions were: did the Terre

Haute tornado indeed act alone? And what was the full extent of its path of

destruction? To research those questions, a year ago (April 2014), I photocopied

articles on the Terre Haute tornado from microfilmed pages of 10 local 1913

newspapers in Vigo and surrounding counties housed at the Indiana State Library in

Indianapolis.

The path of the Terre Haute tornado never was mapped

either at the time or later—or if it was, such a map seems never to have been published

in local newspapers or in Monthly Weather

Review, the official journal of the U.S. Weather Bureau. But the commemorative booklet Terre Haute’s Tornado and Flood Disaster, March twenty-three to thirtieth, nineteen hundred and thirteen issued by the Terre

Haute Publishing Co. and heavily relying on newspaper accounts and photographs,

compiled many individual stories—many of which include names and street addresses

of victims and of buildings destroyed.

|

| Cover of the commemorative booklet Terre Haute’s Tornado and Flood Disaster, March twenty-three to thirtieth, nineteen hundred and thirteen issued by the Terre Haute Publishing Co. Street addresses in this booklet allowed me to plot the destruction of the tornado through Terre Haute. Credit: Wabash Valley Visions and Voices |

So with the aid of Google Maps, I spent an entire

day plotting scores of 1913 addresses on a modern map of Terre Haute to see

what emerged.

Several revelations emerged. First, the city of

Terre Haute in 1910 was Boomtown, USA. It had almost the same population as it

does today: over 58,000 compared to 61,000, making it then one of the nation’s top 100 populous cities. It was also growing fast, Even so, its city limits were smaller and surrounded

by fields and farmland instead of urban sprawl and suburbs (today Terre Haute’s

entire statistical metropolitan area encompasses over 170,000 people).

Second, street numbering and names today must differ

on some streets. Google Maps could not plot any of the addresses in the booklet

given for Lockport Road, so those data are missing from my map. Neighborhoods

must have also changed names. For example, the booklet states that tornado

damage was particularly bad in Krumbhaar Place, “the new sub-division recently

opened on the south side of the city”; I could find no subdivision

with that name today, just a single Krumbhaar Street in what might be the approximate

area. Another hard-hit area I could not find was Gardentown (also spelled Garden

Town), apparently an unincorporated community six or eight miles south of the city just

north of Prairieton and largely devoted to truck farming for fruit and

vegetables and greenhouses for florists. Appeal to

readers: If you know more about the historical geography of Terre Haute, please

contact me.

|

Another general view of tornado

destruction in the Terre Haute. Credit: Terre

Haute’s Tornado and Flood Disaster, Wabash Valley Visions and Voices

|

Third, it is clear from the booklet’s text that several

newspaper reporters or other authors sought to be as thorough as possible,

clearly visiting hospitals and walking along ruined streets. But the accounts

are jumpy in geography and some of the anonymous writers were more complete

than others in specifying locations.

Nonetheless, the map I was able to construct of the

tornado’s path of destruction through Terre Haute reveals tantalizing

structure. Are the variations in width due to actual variation in width of the

tornado’s funnel of destruction, or merely incompleteness or limitations in

data gathered or published? Do separations in areas of destruction reveal that

the tornado hopped along its path, or did it just pass through what were open

fields in 1913 until encountering another group of buildings?

And could it have been a multiple-vortex tornado with

several small, short-lived smaller subvortices that orbit around the main

funnel: subvortices that actually deal some of the worst death and destruction?

|

Multiple-vortex tornado

with half a dozen small, short-lived, but exceptionally violent subvortices,

photographed near Altus, OK on May 11, 1982. Credit: U.S. National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

|

A 2013 article by Mike McCormick for the Terre Haute

Tribune-Star written for the

centennial of the Terre Haute tornado describes it as a “multi-funneled

tornado” shortly before 11 PM. But the article cites no reference for either

the time—which is clearly documented as 9:45 PM in Monthly Weather Review and elsewhere—or the assertion about multiple

funnels.

|

Ruins of office of Dr. Mahlon

Moore; if the address given by Mike McCormick is correct, might Moore have been

killed by a subvortex? Credit: Credit: Terre

Haute’s Tornado and Flood Disaster, Wabash Valley Visions and Voices

|

The map of the destruction I compiled from

the booklet, plus the booklet’s stated variations in the width of

destruction, is tantalizingly suggestive of the cycloidal marks carved into farm

fields from multiple-vortex tornadoes.

|

Cycloidal marks in farm fields left by a

multiple-vortex tornado. Credit: U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration (NOAA)

|

Both the booklet and local newspapers published

immediately afterwards in and around Vigo County and in Indianapolis clearly

describe additional tornado destruction in and north of Prairieton—a town of

about 700 population 8 to 10 miles southwest of Terre Haute. The Brazil Daily Times and The Crawfordsville Journal also detailed

damage in Perth, an even smaller town (400 population) about 20 miles northeast

of Terre Haute, as well as in Glenn and East

Glenn, the western part of Seelyville, and Ehrmandale in between. The

northeasternmost report of damage was a mile and a half west of Carbon.

Plotting those areas on a broader-area map suggests

that the path of the Terre Haute tornado could have been 25 to 30 miles

long, as the paths line up nicely. There is also the possibility of the three

areas of destruction being wreaked by different twisters, but almost no

newspaper accounts indicate the time locations were hit, which would be

essential in sorting out the truth.

Plotting specific locations on the streets of

Prairieton, Seelyville, and Perth was almost impossible: in such small

communities, clearly everyone knew everyone else and local landmarks, so

destruction is described only by giving the owners’ names without street

addresses or just the names of local parks long gone. That makes it almost

impossible for someone a century later without detailed knowledge of local

history or access to public records of property ownership to map the extent of

damage. Again, I welcome contact from any reader who can help.

Why was more information not preserved about the

path and timing of the Terre Haute tornado? Reporters in Omaha and Council

Bluffs and elsewhere did history a huge service in preserving a very detailed

and thorough record of the family of 10+ tornadoes that struck Easter night

1913. Why is the record sketchier in Indiana?

|

Ruins of Olson house. Note

umbrellas, as it was raining hard and flooding followed a couple of days later.

Credit: Credit: Terre Haute’s Tornado and

Flood Disaster, Wabash Valley Visions and Voices

|

The answer dawned when I was photocopying the newspapers

on microfilm in the Indiana State Library: tragically, the city of Terre Haute

was unique in suffering both violent

tornado damage (like Nebraska, Iowa, and Missouri) and record flooding (like Ohio and other states) in the Great

Easter 1913 storm system. Indeed, Indiana, like Ohio, was at the epicenter of

the 1913 flood. On Easter Sunday, rain in Terre Haute was already heavy, and

floodwaters began overflowing river banks the next day. Not only did record-high

floodwaters confront Terre Haute residents with more urgent worries than

tracing a tornado’s path through the open countryside, but also nature itself was

immediately obliterating that very evidence.

Death

undercount

Published death counts for the Terre Haute tornado

range from 17 to 21. Seventeen—the number given in the booklet—is a clear

fact-checking error and significant undercount: simply cross-checking the names

of fatalities described in the booklet’s text with the names given in “Toll of

the Tornado” reveals the omission of at least three people whose bodies were

discovered: Mrs. Moses Carter and Mrs. Leonard Sloan and her day-old infant. Also, The Crawfordsville Journal reported

“one or more” people killed in Prairieton. So the verified minimum

is no fewer than 20 killed, and perhaps closer to 23.

And of course, as discussed already in a detailed

analysis of fatalities during the Great Easter 1913 storm system and flood (see “‘Death Rode Ruthless…’” ), people injured by the Terre Haute tornado could have died weeks or even

months later of complications and thus not have been counted as tornado deaths at the time the booklet was published.

© 2015 Trudy E. Bell

Next

time: Never Before Seen

Selected

references

Special thanks go to Ray Thomas for high-resolution

scans of the New York Underwriters Agency leaflet and permission to use images from his amazing website of postcards from the 1913 flood.

In addition to the sources already cited in the

text, these also proved especially useful:

“Big Storm Passes West of Brazil” and “Damage Near

Carbon,” both in The Brazil Daily Times, March

25, 1913, p. 1.

Edwards, Roger, “The Online Tornado FAQ,” U.S. National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Grazulis, Thomas P., Significant Tornadoes, 1880-1989. St. Johnsbury, VT: Environmental

Films, 1991. Classic and fascinating two-volume reference detailing virtually

every U.S. tornado F2 and greater for more than a century. Grazulis now runs The

Tornado Project.

“Perth in Path of Disastrous Storm” The Brazil Daily Times, March 24, 1913,

p. 1.

Shannon, Charles W., “Soil Survey of Clay, Knox, Sullivan

and Vigo Counties, Indiana,” Thirty-Sixth

Annual Report of Department of Geology and Natural Resources, Indiana 1911, Indianapolis,

1912, pp. 137–280. Brief description of Garden Town is on page 275.

“Tornado and

Flood Damage at Terre Haute, Ind.,” Engineering

News 68(15): 738–739, April 10, 1913.

“Tornado at Terre Haute, Ind., March 23, 1913,” Monthly Weather Review 41(3): 483–484,

March 1913.

Bell, Trudy

E., The Great Dayton Flood of 1913, Arcadia Publishing, 2008. Picture

book of nearly 200 images of the flood in Dayton, rescue efforts, recovery, and

the construction of the Miami Conservancy District dry dams for flood control,

including several pictures of Cox. (Author’s shameless marketing plug: Copies

are available directly from me for the cover price of $21.99 plus $4.00

shipping, complete with inscription of your choice; for details, e-mail me), or

order

from the publisher.